Executive summary

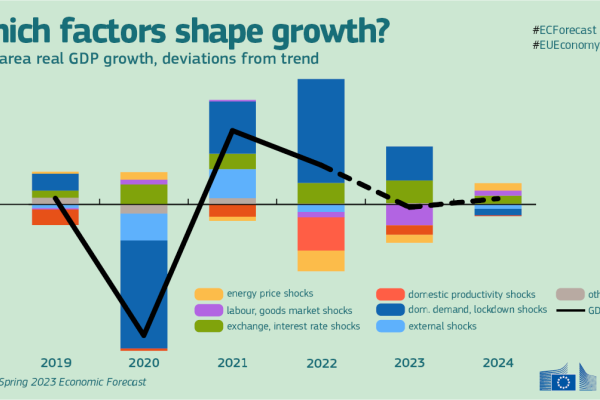

Over the past winter, the EU economy performed better than expected. As the disruptions caused by the war in Ukraine and the energy crisis clouded the outlook for the EU economy, and monetary authorities around the world embarked on a forceful tightening of monetary conditions, a winter recession in the EU appeared inevitable last year. The Autumn 2022 Forecast had projected the EU economy to contract in the last quarter of 2022 and the first quarter of 2023. Instead, latest data point to a smaller-than-projected contraction in the final quarter of last year and positive growth in the first quarter of this year. The better starting position lifts the growth outlook for the EU economy for 2023 and marginally for 2024. Compared to the Winter 2023 interim Forecast,

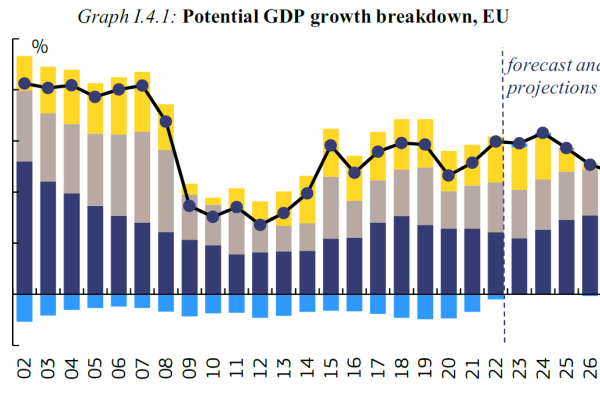

EU GDP growth is revised up to 1.0% in 2023 (from 0.8%) and 1.7% in 2024 (from 1.6%), virtually closing the gap with potential output by the end of the forecast horizon (see Special Issue I.4.1). Upward revisions for the euro area are of a similar magnitude, with GDP growth now expected at 1.1% and 1.6% in 2023 and 2024 respectively. Inflation also surprised again to the upside, and it is now expected at 5.8% in 2023 and 2.8% in 2024 in the euro area, respectively 0.2% and 0.3% higher than in winter.

Model-based analysis suggests that the improved outlook is driven by the terms-of-trade countershock caused by declining energy prices, while broad price-increasing supply-side factors lead to inflation persistence (see Box I.2.4). Recent economic developments seem to corroborate these results. According to Eurostat’s preliminary flash estimate, in 2023-Q1 GDP grew by 0.3% in the EU and by 0.1% in the euro area, a notch above the Winter interim Forecast projections. Lower energy prices, abating supply constraints, improved business confidence and a strong labour market underpinned this positive outcome. As for inflation, the headline index continued to decline in the first quarter of 2023, amid sharp deceleration of energy prices, but core inflation firmed, pointing to persistence of price pressures. For the second quarter, survey indicators suggest continued expansion, with services clearly outperforming the manufacturing sector and consumer confidence continuing its recovery from last autumn’s historical low.

The EU weathered the energy crisis well thanks to the rapid diversification of supply and a sizeable fall in consumption (see Box I.2.1). As the EU approaches the gas-refilling season, gas storage levels are at comfortable levels and risks of shortages during next winter have considerably abated. Further supply diversification and the accelerated increase in renewable power generation are expected to allow the EU to continue replacing fossil-based sources, including gas, while reducing the likelihood of renewed price pressures.

At the cut-off date of this forecast, wholesale gas prices were projected to be 25% and 13% lower in 2023 and 2024 respectively, compared to markets’ expectations at the time of the previous Commission forecast. Oil prices were also expected to be 10% lower, compared to early February, in both 2023 and 2024.

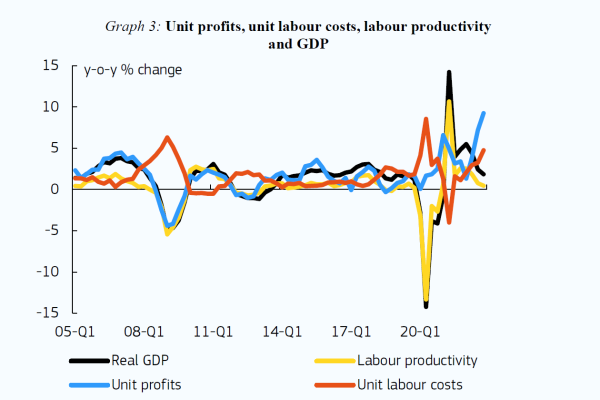

The sharp deterioration of terms of trade in 2021 and 2022, as energy (imported) prices surged, resulted in a transfer of purchasing power from the EU to the rest of the world. With energy prices rapidly falling, the expected improvement in terms of trade over the forecast horizon will drive a reversal of this effect, to the benefit of all domestic sectors of the economy – households, corporates and governments. So far, households and public finances have taken a large part of the brunt of high imported inflation, as employment growth only partially offsets the fall in real wages and public finances set out to protect households and corporations from the adverse impact of high energy prices. Companies have been generally successful in passing on higher production costs to consumers (see Box I.2.3). However, the most energy-intensive sectors and companies have been struggling. Going forward, households are set to see their real disposable incomes finally increase in 2024, while falling energy prices allow governments to contain the cost of support measures or phase them out altogether.

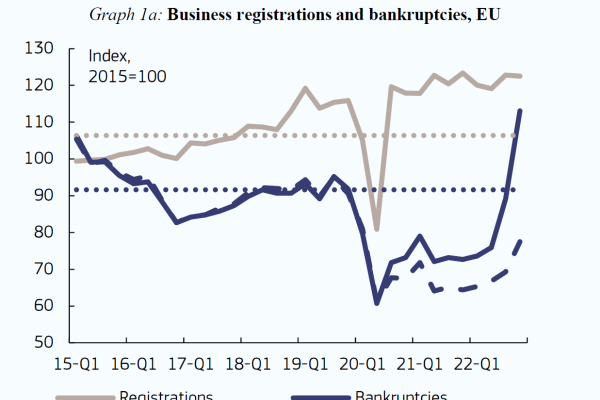

The progressive firming of core inflation has set EU monetary authorities on a path of more forceful monetary tightening. In its meeting of 5 May – i.e. shortly after the cut-off of this forecast – the ECB Governing Board lifted policy rates by 25 basis points, down from 50 basis points in the previous two rounds of policy hikes. This was largely anticipated by market agents. At the cut-off date of this forecast, the euro area short-term rate was expected to peak at 3.8% in 2023-Q3, before abating in the course of 2024. Long-term interest rates have hardly moved. Tighter monetary conditions are feeding through the credit channel: borrowing costs are increasing, while credit flows are decreasing. The collapse of Silicon Valley Bank and two other US banks and the problems with Credit Suisse compound with the effects of higher policy rates. While well-capitalised and thoroughly supervised, EU banks’ declining risk tolerance is expected to lead to a further tightening of lending standards. As usual, projections about interest rates underpinning this forecast reflect market expectations at the time of the forecast. Moreover, this forecast assumes an orderly adjustment of the financial sector to higher policy rates, while risks stemming from exposures to households and corporates are assumed to be manageable (see Box I.1.1). While bankruptcies increased significantly towards the end of last year, the surge largely reflects a clearing of the insolvency backlog created by support schemes during the pandemic and country-specific developments related to changes in insolvency regulations (see Box I.2.2).

The tightening of financing conditions is expected to weigh on investment over the forecast horizon.

Housing investment, which is particularly sensitive to interest rates, is set to contract. By contrast, business investment is projected to still increase, though at a slower pace than last year, helped by corporates’ overall healthy balance sheet position. Finally, public investment is forecast to remain buoyant in both 2023 and 2024 thanks to the continued deployment of the Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF). Overall, investment growth is projected to decelerate markedly from 4% in 2022 to 0.9% in 2023. Gradual normalisation of economic activity is expected to reinvigorate companies’ investment decisions, pushing overall investment growth up by 2.1% in 2024.

Inflation keeps eroding the purchasing power of consumers. Following the fall in the last quarter of 2022, private consumption is expected to have weakened again in the first quarter of this year. Overall, private consumption growth in the EU in 2023 is projected at 0.5%. As inflation loosens its grip on households’ budgets, private consumption is set to rebound to 1.8% in 2024. The household saving rate is projected to decrease in the EU from 13.2% in 2022 to 12.8% in 2024, in line with its long-term average.

The slower pace of economic expansion in the EU is set to have a limited impact on the EU labour market. Continued labour market tightness, labour hoarding due to skill shortages as well as strong demand, especially for services, are expected to cushion the impact of the economic slowdown on the labour market.

Employment growth is still forecast at 0.5% in the EU this year. In 2024, employment is set to keep growing moderately (0.4%), implying a less job-rich growth than in 2022. The unemployment rate is expected to remain close to its historical low, at 6.2%, in the EU in 2023, before edging down to 6.1% in 2024.

After growing by 5.0% in 2022, the annual growth rate of compensation per employee is projected to increase to 5.9% in 2023 before falling to 4.6% in 2024. This means that real wages are still set to decrease this year, though a slight pick-up in real wages is expected towards the end of the year.

Sharply lower natural gas prices are making their way to retail prices of gas and electricity, though at varying speeds across EU Member States. At the same time, all other major inflation subcomponents (processed and unprocessed food, non-energy industrial goods and services) have seen their annual inflation rate increase between December and March. Consequently, core inflation (headline excluding energy and unprocessed food) continued to rise in early 2023, to a historical high of 7.6% in March, and core goods and services replaced energy as the primary driver of headline inflation in the EU. Recent indications on managers’ selling price expectations from business surveys and other indicators corroborate the projection of core inflation having peaked in the first quarter. Core inflation is projected to decline gradually as profit margins absorb higher wage pressures and tighter financing conditions prove effective. Average core inflation in 2023, at 6.9% in the EU, is set to exceed that in 2022, before falling to 3.6% in 2024, above headline inflation in both forecast years.

The economic expansion and reduced pandemic-related emergency measures supported the further reduction of the EU government deficit in 2022, to 3.4% of GDP, despite the expansionary fiscal stance driven by sizeable energy support measures.

In 2023 and especially in 2024, the phasing out of energy support measures is expected to drive further deficit reductions on aggregate in the EU, to 3.1% and 2.4% of GDP,

respectively, and the corresponding fiscal impulse should turn contractionary. However, several Member States are still projected to see a deterioration in their general government balance in 2023, as their fiscal stance remains expansionary. While falling energy prices are helping to contain the cost of existing support measures, several Member States have introduced new energy support measures or are extending existing ones. Furthermore, while inflation supported the improvement in the government balance ratio in 2022, some reversal of this effect is expected in 2023 as large expenditure items like pensions and other social transfers, as well as public wages, are adjusted to the previous’ year inflation. In 2024, on account of unchanged policies, the deficit reduction is set to be broad-based across countries. Meanwhile, the EU aggregate debt ratio is expected to fall in 2023-24 despite debt-increasing primary deficits, thanks to economic growth and inflation. Higher interest rates are affecting the cost of servicing public debts only gradually thanks to their long maturity.

The EU debt-to-GDP ratio fell to around 85% of GDP in 2022, from the record high of 92% recorded in 2020. It is projected to further decline to below 83% of GDP in 2024, but to remain above the pre-COVID-19 crisis level of around 79% in 2019.

Global growth, excluding the EU, is expected to fall from 3.2% in 2022 to 3.1% in 2023, before rising back to 3.2% in 2024, broadly unchanged since the Winter interim Forecast. The outlook for external demand facing the EU has however been significantly downgraded, as synchronised weakness in advanced economies (and especially in the US) weighs heavily on EU exports. The rebound in economic activity in China, moreover, is set to benefit primarily the domestic sectors, services in particular, with limited positive spillovers to the EU. Still, net external demand is expected to contribute positively to GDP due to weak import dynamics – especially for goods in 2023. The current account balance is set to improve steadily from the record-low surplus of 1.6% of GDP in 2022 to 3.5% in 2024. The improvement is mainly driven by the merchandise trade balance, which is forecast to turn positive this year and improve further next year, largely as a consequence of falling import prices. The services trade balance is forecast to remain strong throughout the forecast horizon, with tourism being a strong driver of the economic rebound. This publication includes for the first time an overview of the economic structural features, recent performance and outlook for Ukraine, Moldova and Bosnia and Herzegovina, which were granted candidate status for EU membership by the Council in June 2022 and December 2022 (see Special Issue I.4.2).

While the outlook in our central scenario has not changed much since last winter, downside risks to the economic outlook have increased. Persistence of core inflation has emerged as a key risk. It could continue restraining the purchasing power of households and force a stronger response of monetary policy, with broad macro-financial ramifications. Moreover, a surge in risk aversion in financial markets, following the banking sector turmoil originated in the US, could prompt a more pronounced tightening of lending standards than assumed in this forecast. In this context, policy consistency has become even more important. An expansionary fiscal policy stance would fuel inflation further, leaning against monetary policy action. In energy markets, the threat of outright supply shortages for next winter has significantly abated, but the evolution of prices remains highly uncertain. More benign developments in energy prices would lead to a faster decline in headline inflation, with positive spillovers on domestic demand. Risks related to EU’s external environment remain unusually elevated, with new uncertainties following the banking sector turbulence or related to wider geopolitical tensions. Finally, there is persistent uncertainty stemming from Russia’s ongoing invasion of Ukraine.

The EU economy is in better shape than we projected last autumn. We avoided a recession and are set for moderate growth this year and next. Yet risks are too plentiful for comfort: we must remain vigilant.

Special Issues - Spring 2023

Thematic boxes - Spring 2023